Image credit: Mathias Reding

The fashion industry is responsible for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to the United Nations. At its current trajectory, the industry’s emissions could rise to 26% or a quarter of the world's carbon budget by 2050. Deemed one of the most polluting industries in the world, it uses 342 million barrels of oil (fossil fuels) to make synthetic textiles. It produces greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to around 1.2 billion tonnes of CO2 each year – more than shipping and aviation combined. Despite fashion’s contribution to climate issues, it’s not always included in top level climate discussions.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s 30th annual Conference of Parties aka COP30, is the world’s largest and most important annual climate conference with nearly 200 nations is running from November 10 to 21, 2025. The host country, Brazil, insisted that this year’s summit must lead to ‘implementation’, calling it “the COP of implementation”. In addition to setting this year’s COP30 agenda, Brazil also holds the current presidency of BRICS countries- the economic and political trade cooperation bloc made up of ten emerging economies. The COP30 agenda is structured around several themes, three of which relate more closely with fashion emissions:

Transitioning energy and industry is about transitioning away from fossil fuels towards clean energy sources. The connection with the fashion industry relates to the reliance on fossil fuels for the production of synthetic textiles such as polyester being a significant driver of climate change.

Stewarding forests, oceans, and biodiversity focuses on protecting ecosystems, ending deforestation and acknowledging the role of these areas in climate regulation. The fashion industry is a culprit here because it relies on these ecosystems for raw materials and water, yet its practices such as deforestation, pollution, and resource-intensive production severely damage them. This creates a cycle of degradation, biodiversity loss and destruction of ecosystems, which undermines the very natural resources it depends on and exacerbates climate change.

Unleashing enablers and accelerators, including finance, technology and capacity building covers guidelines of climate action, such as mobilising climate finance, developing and deploying technology and building capacity. This can provide a framework for the fashion industry to minimise its greenhouse gas emissions, aligning with goals such as those of set by the UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action and the Paris Agreement.

Image credit: Marcus Loke

Australia’s fashion overconsumption and COP30 commitment

In regards to fashion and emissions, Australia is one of the biggest consumers of fashion and most wasteful in the world per capita. Australia is also in attendance at COP30 and has committed to Brazil’s leadership in the COP30 agenda which addresses some fashion-related climate issues:

deliver the clean energy transition

further reduce global emissions

strengthen adaptation efforts

mobilise resources for climate finance

unlock investment in clean energy solutions for Australia and our region.

BRICS green manufacturing agenda can provide a framework for the sustainable development of Australia and the global textiles & fashion sector.

BRICS’ sustainable governance declaration

In July 2025, BRICS’ ten-member states (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Egypt and Iran) held a meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The bloc’s meeting reaffirmed their commitment to the objectives of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement in tackling climate change and mitigating, adapting and providing the means of implementation to developing countries. In Rio de Janeiro, the bloc produced a declaration, ‘Strengthening Global South Cooperation for a More Inclusive and Sustainable Governance’ also known as BRICS Leaders Declaration detailing a set of climate policies specifically targeted at the negotiations at COP30 in the city of Belem, in Brazil in November 2025. These policies of climate finance, carbon accounting, energy transition and a multilateral sustainability platform are additionally suitable for addressing fashion’s emissions and pollution problems.

In a statement addressing Brazil’s COP30-BRICS climate convergence, the Interim Executive Director, World Resources Institute, Brazil Mirela Sandrini said “Brazil deserves credit for bringing the BRICS together behind a more assertive vision for climate action. Brazil is deftly weaving climate diplomacy into the fabric of broader global agendas – from its G20 Presidency to BRICS and soon the COP30 summit. This integrated approach helps reduce fragmentation across international fora and positions climate policy as a cornerstone of global economic and financial reform – driving the inclusive, green growth the world urgently needs.”

BRICS to COP30 climate policies (à la fashion)

Climate finance

Strengthening climate finance, increased climate lending and deeper green bond markets are one of the BRICS’ climate policy asks. The BRICS declaration emphasised “ensuring accessible, timely and affordable climate finance for developing countries is critical for enabling just transitions pathways that combine climate action with sustainable development.” This means advancing the existing responsibility of mobilising and providing resources from developed countries towards developing countries under the UNFCCC and its Paris Agreement.

The declaration includes the objective to strengthen pathways and mechanisms that involve and incentivise private sector climate finance & investment efforts and complement public finance flows to this mission.

It’s assumed that the declaration’s climate policy is reinforcing the agreement created at COP29 in 2024 for a new climate finance goal, New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). This was designed to provide USD $300 billion annually by 2035 to developing countries with a bigger target for all actors both in public and private sectors to mobilise a minimum of USD $1.3 trillion by 2035; far closer to the amount developing countries need for the mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.

Climate finance stems from wealthier nations historically contributing far more to climate change. Critics such as Oxfam have raised concerns that the mix of private investment and loans under climate finance could lead to more debt for vulnerable developing nations rather providing fair and equitable financial climate support.

The July BRICS declaration addresses debt around international financial cooperation, saying “High interest rates and tighter financing conditions worsen debt vulnerabilities in many countries. We believe it is necessary to address the international debt properly and in a holistic manner to support economic recovery and sustainable development….”

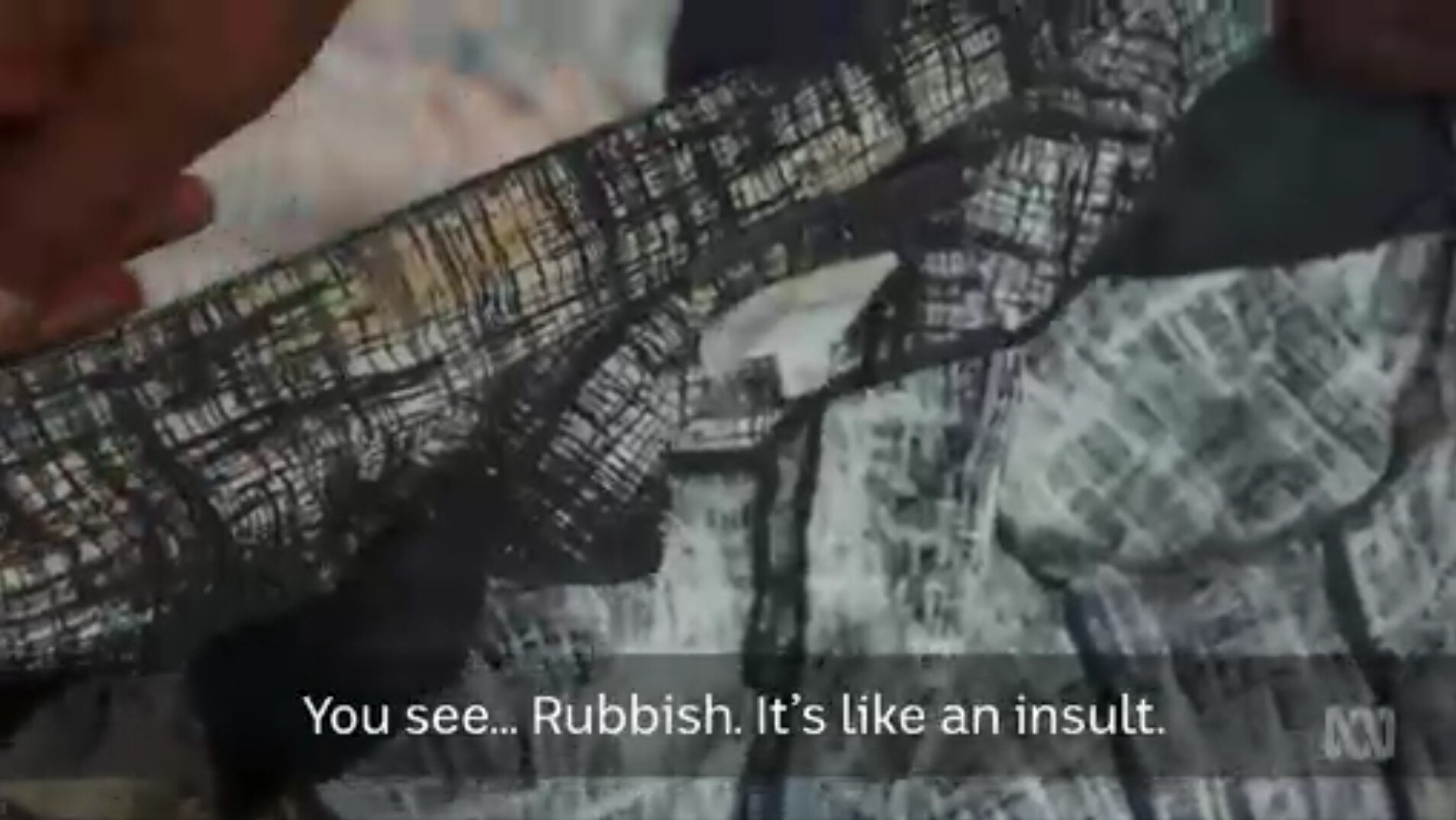

If implemented correctly, there are a plethora of ways that climate finance can be useful in salvaging the environment from fashion’s harmful operations. According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), every year, as many as 4 million tonnes of used textiles are shipped across the planet from North to South. Around 40% of imported clothing bundles are unsellable, unusable and unwearable according to Greenpeace. They are immediately destined for landfill, incineration or end up polluting beaches and waterways. Climate finance could mitigate a significant amount of the environmental impact of this waste stream.

Energy Transitions – Reaching adequate, predictable and accessible low-cost and concessional finance to bridge the funding gap for energy transitions is one of the bloc’s summit priorities. As manufacturing is a major and fundamental aspect of fashion production, the industry’s sustainability can benefit significantly from finance for energy transitions.

Carbon accounting

The declaration pushes for a mutually recognised system, methodologies and standard for assessing greenhouse gas emissions for a more balanced international approach by manifesting the BRICS Principles for Fair, Inclusive, and Transparent Carbon Accounting. It focuses on creating carbon accounting standards for product and facility footprints that consider diverse circumstances of different nations. The standard most used in the fashion industry for carbon accounting is potentially the ISO 14067 which provides a framework for only calculating a product's carbon footprint through a "cradle-to-grave" lifecycle assessment (LCA) but does not include the facility’s footprint, nor associated circumstances.

Multilateral climate, sustainability & trade platform

The BRICS Laboratory for Trade, Climate Change and Sustainable Development is a platform for collaborating on mutually supportive approaches to trade and environmental policy. It enables BRICS members to not only benefit from trade but also collectively respond to unilateral measures and contribute to global efforts in addressing environmental challenges.

This can serve as a model for a new unified international fashion platform or for existing organisations, such as the UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, to either step up or create a coordinated agenda of environmental policy, legislation, sustainable trade and global best practice principles. Different countries have been passing various forms of legislation, creating policies and programs for trade to combat the harm done by the fashion industry. It could be highly effective to have a global sustainable fashion platform.

As COP30 has been designated the ‘COP of implementation’ along with the BRICS declaration climate policies for the climate summit, fashion might be able to adopt these measures to advance positive climate and environmental outcomes.

Article by Nina Gbor